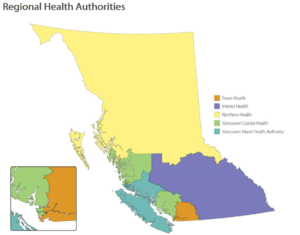

Effective regulation is a tenet of a multiple-barrier approach to clean, safe, and sustainable drinking water (Figure 1). In British Columbia, regulation of community water supplies is accomplished through a variety of Acts and Regulations depending on the type of ownership. However, the principle legislation for safety in all drinking water supply systems is the Drinking Water Protection Act and Regulation (SBC 2001, C.9).

Figure 1: A multi-barrier approach to safe drinking water includes regulation. In BC regulation is done under the Drinking Water Protection Act (SBC 2001, C.9)

Figure 1: A multi-barrier approach to safe drinking water includes regulation. In BC regulation is done under the Drinking Water Protection Act (SBC 2001, C.9)

The Drinking Water Protection Act (DWPA) is an outcome-based legislation. There are some specific requirements (e.g. permits; emergency response and contingency plans), but the legislation generally avoids prescribing how water suppliers go about making water safe. An outcome-based regulation affords flexibility for cost-effective services to users; it also includes a significant amount of discretion. This discretion can be challenging for those tasked with enforcing the regulation, requiring understanding of the circumstances faced by each individual system.

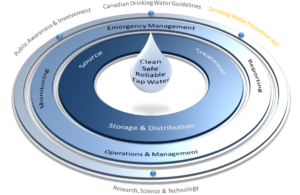

To ensure understanding of individual system the DWPA employs a delegated decision maker model that places authority in the hands of local Drinking Water Officers, rather than centralizing authority in senior leaders. Drinking Water Officers (DWO) can enforce all aspects of the DWPA. Given the DWPA is focused on human health, Medical Health Officers (MHOs) are the principal DWOs for their respective health regions. MHOs are Medical Doctors who specialize in community medicine. Though MHOs work for the five regional Health Authorities (Figure 2) their authority comes directly from the BC legislature as an Order in Council.

As you might expect, MHOs are very busy. They respond to all health issues within our communities, including all communicable diseases and hazardous substances. MHOs delegate their authority to Health Authority staff to act as DWOs and regulate community water supplies. The top priority is timely investigation and response to disease outbreaks. As such, delegated DWOs must have core skills in environmental health investigation, risk assessment and application of public health law. Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) are commonly delegated the role of DWO as they are nationally certified with degrees in Environmental Public Health.

Figure 2: British Columbia Regional Health Authorities

Under the DWPA public and private water system owners are responsible for ensuring their water is safe, including ongoing monitoring and implementing necessary system upgrades. While the legislated requirements of drinking water systems are exactly the same in all BC health authorities, the challenges water suppliers face differ. Geography, historic development, and ownership type all shape the challenges water suppliers face in each region of our province.

As an example, the Interior Health (IH) authority region has over 750,000 residents served by 1,944 permitted water supply systems. Approximately 40% of all the permitted water supply systems in BC are located within the IH boundaries. The IH drinking water systems program provides services to community water suppliers through two teams supported by administrative staff and a small group of public health engineers. One team of four EHOs provides focused service to the 81 largest systems serving over 80% of residents. A team of eight EHOs across IH serve 1,413 small water supply systems, the majority of these systems having fewer than 15 connections.

The IH drinking water program core objectives align with the BC’s Guiding Framework for Public Health, the provincial framework for supporting the overall health and well-being of British Columbians and a sustainable public health system. Specifically, they focus on improving safety by implementing the BC Action Plan for Safe Drinking Water and working to improve stewardship of water through partnership. The ultimate goals of the IH drinking water systems program are to reduce economic and social costs arising from non-compliance, increase safeguards to protect public health, and reduce waterborne disease. The IH DWOs apply a progress compliance approach seeking to regulate with communities. As such, resources are focused firstly on collaboration (e.g. committees, research and education partnerships, and technical support) and secondarily on permitting, inspection and, when necessary, emergency response and investigation.

In 2017 the IH Chief MHO published a report on the state drinking water in the region. The report found outbreaks of drinking water disease common in the 1980s and 90s are no longer occurring. The disappearance of these outbreaks has corresponded with system improvements and increased regulation, including precautionary drinking water advisories (i.e. Boil Water Notices). A large portion of IH residents continue to be subject to water advisories due to poor water quality and water system deficiencies, and it is certain than some people are still getting sick from their drinking water. The report attributes these ongoing exposures to the lack of appropriate safeguards under a multiple-barrier approach. The report provides recommendations for improvement to be implemented by the IH drinking water systems program, including ensuring all large surface water systems achieve provincial treatment objectives by 2025.

For more information on the IH Chief Medical Health Officer’s report visit www.drinkingwaterforeveryone.ca. For more on DWOs and how drinking water is regulated in BC, visit www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/air-land-water/water/water-quality/drinking-water-quality/how-drinking-water-is-protected-in-bc

By J. Ivor Norlin B Tech, Manager, Drinking Water Systems Program, Interior Health Authority

To see the full Operator Digest – click here.